Originally published in MRIN Journal, Issue 5 (2025). This enhanced version includes additional images from Ray Meeker and videos by Adil Writer and the ANAB archives, published with permission from MRIN.

The ancient Indian manuscript Skanda Purana mentions the term Yugantagni, a transformative fire that marks the end of a cycle of creation and its transition into a new cosmic cycle. In various Indian yogic traditions, fire signifies not only that which destroys but also that which purifies and clears the way for a new beginning. Both these themes are present in the astonishing practice of Ray Meeker—artist, architect, educator, practitioner of fire. Throughout his time since journeying overland through Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan to arrive eventually in South India in March 1971 as a young man of twenty-six years, Ray has repeatedly transformed through, and been transformed by, fire. At the same time, his incredible body of environmentally themed sculptural work and monumental installations have repeatedly drawn attention to the Yugantagni—mankind’s constant flirtation with fire, leading it to the tipping point, perhaps to the culmination of an era, a yuga.

Ray had only intended to be in India long enough to build a kiln for his then-friend, Deborah Smith, who was trying to set up a pottery unit there. India’s languid pace conspired to keep him longer—bricks ordered to build the kiln took six months to arrive! Ray stayed on, constructing the first buildings of what would in time become the institution known as the Golden Bridge Pottery (GBP). And yes, over the next five decades, building a remarkable life with Deborah Smith in Pondicherry, India.

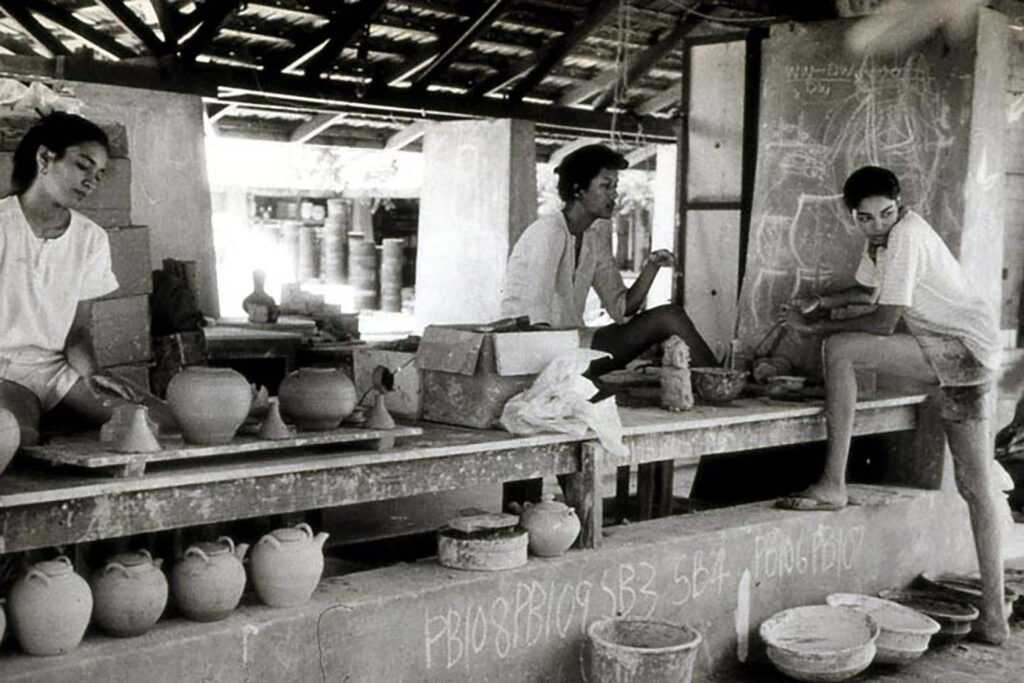

Ray’s time in India could be divided into several, often overlapping roles and radical reinventions. From 1971 to 1982 he partnered Deborah in setting up the buildings, kilns, and production unit at GBP—this included making and decorating most of the production ware at GBP for several years; from 1985 to 1997 he brought architecture and ceramics together in his path-breaking experimentation on “Fired Houses”, comprehensively documented in the award-winning movie Agni Jata (Agni Jata won a bronze medal at Ceramics Millennium, Amsterdam, 1999) and the book Building with Fire (by Ray Meeker, published 2018, CEPT University Press). From 1983 to 2016 he taught a yearly seven-month course in studio ceramics that contributed most significantly to the rise of the ceramic artist in the contemporary Indian art landscape. Between 2001 and 2021 he focused on his own art practice, documented largely through five spectacular exhibitions with gallery Nature Morte. While it is not always possible to talk of one of these facets of his practice without referring to the others, this article is focused primarily on his significant body of work as an artist and a sculptor.

Much has been written about the influence of Golden Bridge Pottery on contemporary Indian studio ceramics. The production of high-fired functional tableware set a benchmark of aesthetic and technical standards for studio pottery in India. Immaculately glazed with distinctive brushwork, it drew on Japanese potter Shoji Hamada’s Mashiko ware. With passing years, the dissemination of their vast knowledge of running a production unit, kiln building, and glaze firing resulted in the sprouting of several pottery units in Pondicherry and Auroville, the region becoming synonymous with “Pondicherry pottery”. In 1983 GBP started accepting students to a comprehensive and much sought-after seven-month course; in 1997 they started hosting workshops by an incredible pantheon of international ceramic greats; in 2006 a Japanese-style woodfire “Anagama” kiln was built—the first of its kind in India—by Peter Thompson, their first international artist in residence. Each of these events indelibly imprinted upon the development and maturity of the Indian ceramic scene.

It is incredible to note, however, that Ray didn’t do much pottery or sculpture for more than a decade, between 1984 and 1995. Completely consumed by the Fired House project, Ray spent his energies on a quest for sustainable low-cost housing. Inspired first by Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy’s Architecture for the Poor, and then by Iranian architect Nader Khalili’s Ceramic Houses: How To Build Your Own, Ray undertook what can be seen as pioneering socially relevant architectural research work—a new approach to possible energy-efficient ways of building. I was fortunate enough to assist him on various such projects between 1990 and 1993, and saw this work from a more poetic and lyrical point of view. This was a great dance of form and fire—mellifluous mud sculptures were built in a configuration of domes and vaults; these were then loaded with bricks made from the earth upon which they stood, and terracotta ware fashioned by traditional artisans; finally fired as giant kilns, over days and nights—purified by fire, they were born as homes to live in. Surely a precursor to his explorations at mammoth scale of sculpture and installation work that followed in subsequent years.

In 1996, coming towards the end of the fired house project, Ray began work on what would be his first solo exhibition in India—twenty-five years after his arrival in this country. For this exhibition, held at the Eicher Gallery in New Delhi, Ray chose to showcase his mastery of the functional, through a series of vases, of lidded containers, of platters. The visual aesthetic was still discernibly an extension of the work made at Golden Bridge.

However, one could now see the Japanese in a dance with the Indian—the repetitive motif of mango fruit and mango leaves, blessing the generous forms with their sweetness and auspiciousness; the fish vases, perhaps an ode to the embrace of the Coromandel Coast; the incredibly skilled stacked serving dishes, reminiscent as much of the rising South Indian temple forms as of the humble Indian tiffin carrier. The exhibition was a huge success—much of the work bought by Ray’s students and their families, exhilarated by witnessing the beauty and power of their teacher’s work for the first time.

Don't it always seem to go

That you don't know what you've got, till it's gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

Joni Mitchell, Big Yellow Taxi, 1970

To talk about Ray’s next exhibition, Kurukshetra, in 2001, one needs to travel back in time to when the seeds for it were sown. Back at the end of the 1960s, Ray was studying ceramics at the University of Southern California, smack in the middle of a generational counterculture movement. It was not only a time of challenging prescribed norms, of protesting—against war, against mindless development—but also a time of freedom and self-expression. For those who know their popular music, 1969 was the year of the emblematic Woodstock festival. For those who know their American ceramic history, right there in California, an exceptional group of American ceramic artists, led by Peter Voulkos, had literally reinvented contemporary ceramics through their embrace of Abstract Expressionism.

Ray himself, having spent family holidays in the Sierra Nevada mountains growing up, was profoundly impacted by the polluted skyscape of Los Angeles. When he switched his major from architecture to ceramics, it was natural for him to explore the medium of clay not only through making pots on the wheel, but through large sculptures that fit this political and social context.

By 2000, the dawn of a new millennium, issues of climate change and sustainable models of development had acquired a space within the public consciousness. Themes Ray had been working with in his final year of college were now not only relevant, but urgent.

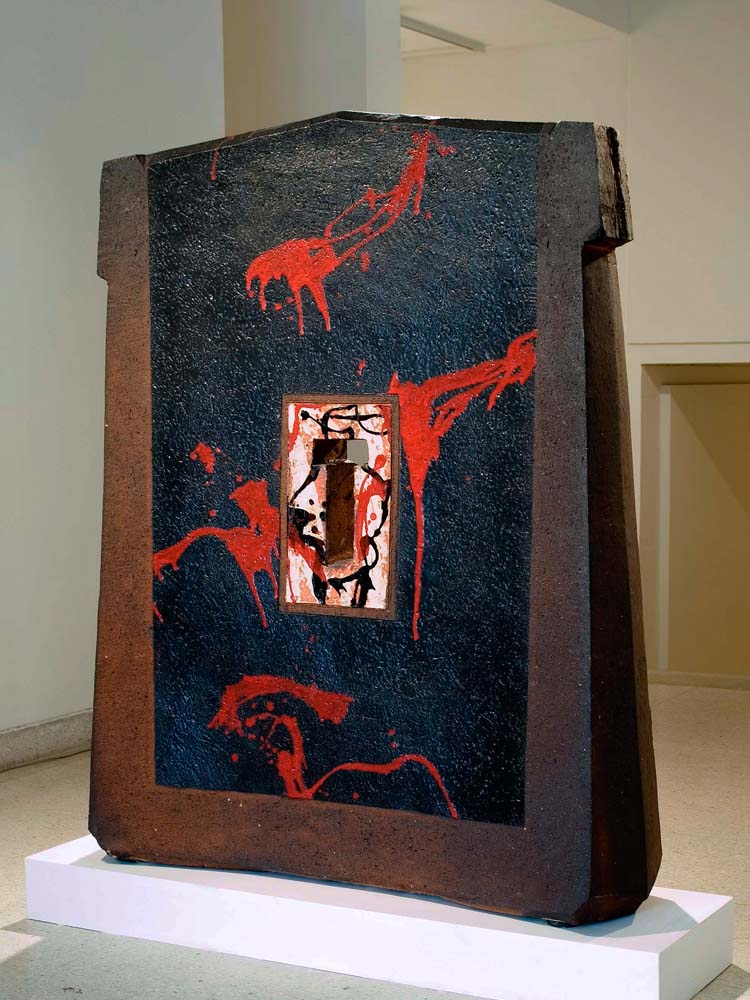

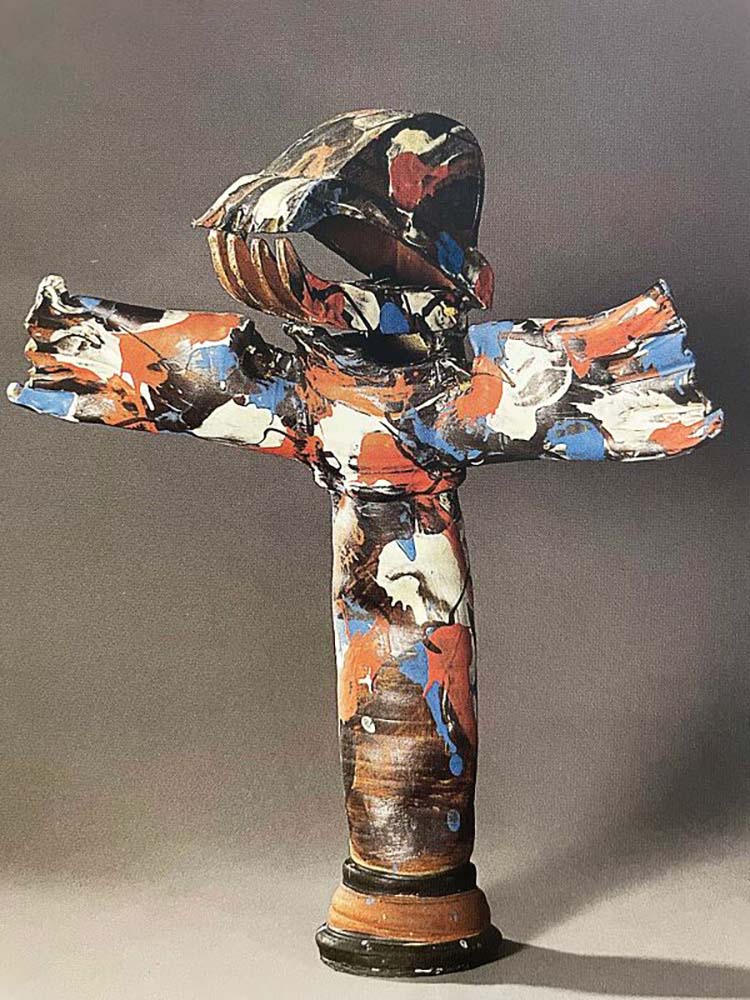

The name ‘Kurukshetra’ comes from the Indian epic Mahabharata, and is the scene of what is referred to as “the righteous battle”. In his own battleground of the gallery space, Ray parked several massive sculptures of excavator buckets. The power of these confrontational, undismissable objects drew grave attention to the battle itself—forces of nature pitted against the force of unmitigated development, upscaled human needs versus unchecked human greed, the clear need for a call to remedy, for recognition and action, against even clearer apathy.

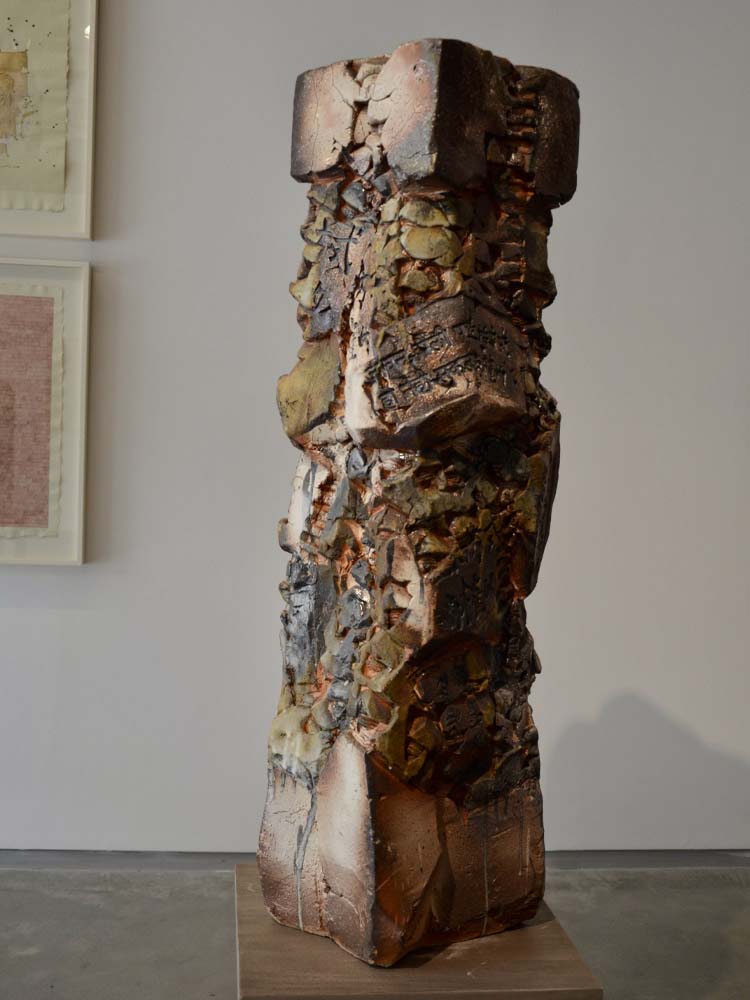

The surfaces of the dark, foreboding sculptures were animated by vigorous splashes of clay slip and dynamic brushwork, accentuating the sense of not just urgency, but of emergency. Along the periphery of this charged space were a series of totems with excavator bucket heads on top, often adorned with necklaces—serving both as the animated face of unchecked, irreversible, and rampant development, as well as emblematic of lost tribes and displaced spirits of a natural way.

No one had ever seen anything like it. The stark departure from the ripe natural beauty adorning the functional pots of 1996 to this stark battleground of 2001 was likened by me in an earlier article to “Bob Dylan going electric for the first time”. While for Ray it seemed like the right time to pick up a relevant thread from his time as a student in 1970, this body of work was not about going back—it was more finding a portal for his future direction as an artist.

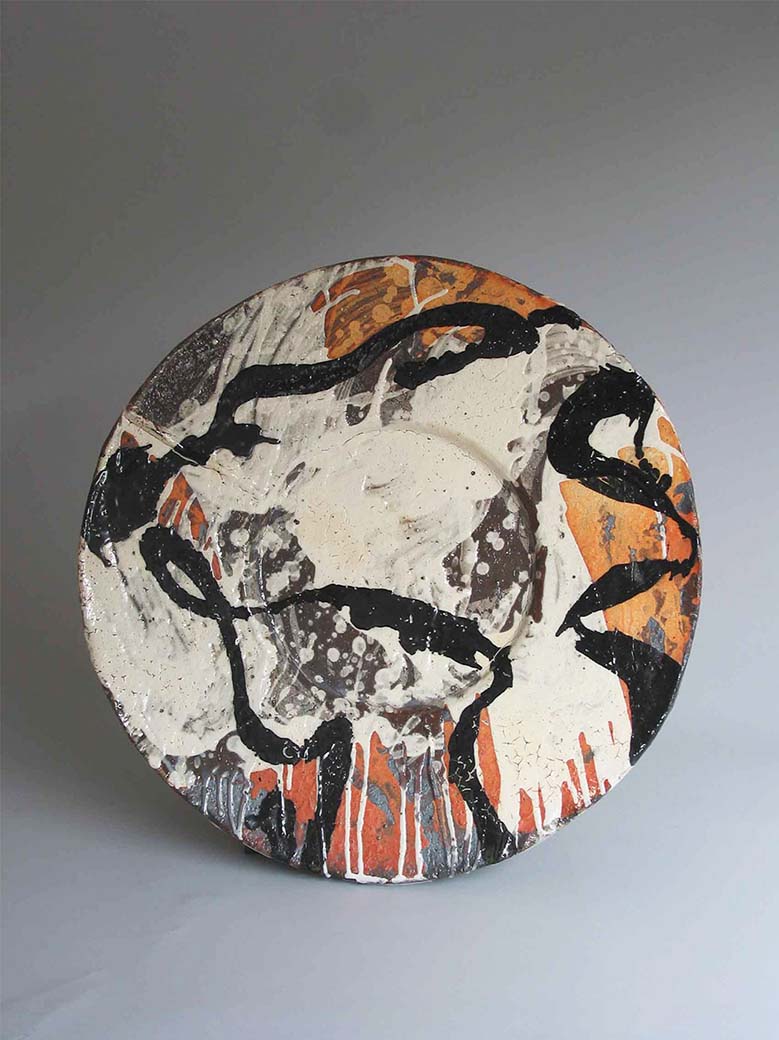

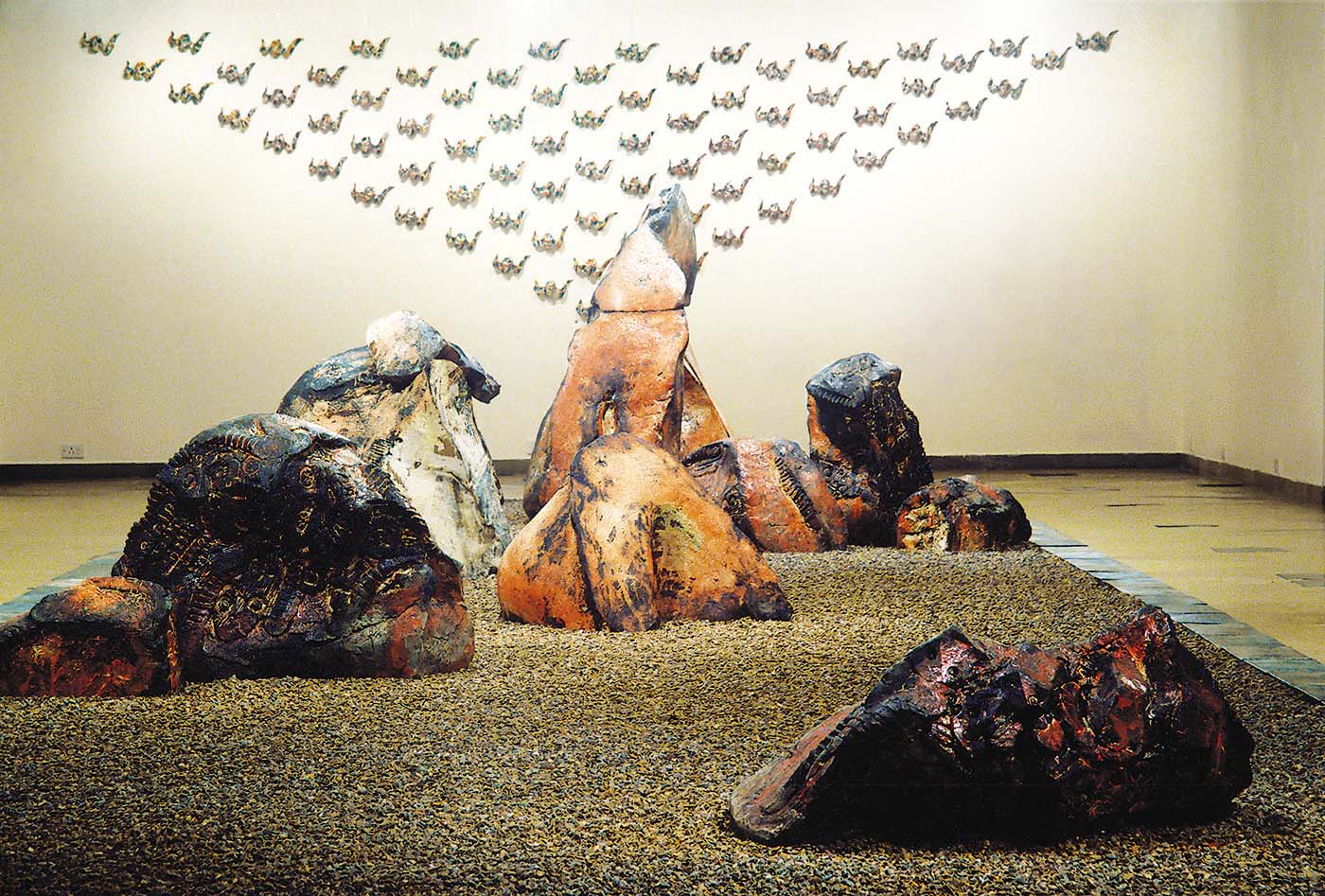

The body of work that Ray showcased in Subject to Change Without Notice, 2004, presented by Nature Morte in collaboration with the Visual Arts Gallery, New Delhi, continued to bring attention to this seeming dance of human self-destruction and nature’s immediate and unforgiving response to it. Inhabiting centre-space was the incredible installation Kyoto Protocol—a post-industrial wasteland in the form of a serene zen garden. The title came from a treaty on climate change signed in 1997, setting legally binding targets for countries to cut emissions. Its efficacy was called into question, as it was not signed by either the United States or China.

The installation constituted a series of large craggy rock-like formations in high-fired stoneware clay, laid out on a bed of gravel. The abstract forms were imprinted with stamps of nuts and bolts and other mechanical markings, suggesting the remnants of a climacteric industrial past. In the background was a formation of ceramic drones surveying this stark post-apocalyptic landscape. It was both a rage against a flawed developmental model, highlighting the stark consequence of such a direction, as well as a silent plea for a life-sustaining model based on co-existence and mutuality. It was industrial zen—the mute reminder of a war memorial; the suggestive peace of an aftermath. The work was political, passionate, and powerful.

Surrounding this central installation were a series of platters, vases, and smaller sculptures, using glaze and fire to masterful effect. Fish continued to inhabit the work—here in a sculpture named Resurrection—perhaps marking the birth of a new yuga, a new cycle of creation.

Outside the gallery was a large permanent sculpture called Hegemony. Inspired by the Avebury stone circle, it both marvelled at and questioned man’s ability to manipulate and dominate. And ultimately to self-destruct, like the ancient symbol of the ouroboros—the snake eating its own tail.

I know there’s a balance,

I see it when I swing past

Between a Laugh and a Tear

John Mellencamp, 1985

Ray’s next exhibition, 2008’s All the King’s Horses…, continued to offer work birthed from an environmental consciousness. Four large lidded jars, based on ancient funerary urns from Tamil Nadu, and made in collaboration with Tamil village potter T. Pazhanisamy, carried images of the earth’s continents on them. The lids were imprinted with the words “The American lifestyle is not up to negotiation”—a documentation of the stance taken by American President George Bush at the Earth Summit in Rio, 1992. The statement was translated and inscribed in Hindi and Chinese, pointing to the perils of these large populations embracing the consumerist model.

In Untitled 1 (Black), a sculptural work with a keyhole in the middle, surrounded by red brushwork splashes on a dark background, Ray continued to outline this tenuous balance between human ingenuity and human insatiability—how this ingenuity was the key that unlocked so much, but at the cost of blood spilt and the death of a natural equilibrium.

If thus far this article has failed to put enough emphasis on the ground-breaking aspect and technical challenges involved in making and firing massive sculptures in clay, Ray’s 2011 outdoor sculpture Passage serves well to highlight Ray’s resolve and technical mastery in facing and overcoming these challenges. Ray, along with scenographer Rajiv Sethi, co-curated a sculpture garden for a new Hyatt Hotel in Chennai, with works by nine ceramic artists. Ray’s own piece Passage took the form of a massive 21-foot-high gateway— inspired by the statuesque temple gateways of South India—marking the entrance of the hotel. It had a seven-foot-high passage one could walk through.

The gargantuan sculpture was made using 17 tonnes of plastic clay. Cut up into several manageable parts that could be fit into the kiln, it was like a gigantic jigsaw that could not be solved or seen in its entirety until its eventual post-firing installation on site. And if any one piece were to be lost during any of the (harrowing) processes of making, drying, firing, transporting, installing on site using cranes—it would be impossible to make and fit again.

While building the piece, special scaffolding was set up to work on each layer of the form. A special low-shrink clay body was tested out, special wooden pallets fabricated, special stackers with hydraulic pumps added to manoeuvre the parts in and out of the kiln. His 140 cu ft woodfire kiln was fired an incredible 50 times over a two-year period (taking into consideration work made by other artists working alongside at GBP for the commissioned garden). Passage marked a pinnacle of Ray’s audacious and adroit large-scale handling of clay.

In 2014, Ray did his fourth exhibition with Nature Morte, titled 71 Running—the age of the artist at the time of the exhibition. The Passage gateway was shrunk down and reimagined as the Eye of the Needle series—a Biblical reference, used to bring attention to the impossibility of human lust for development to sustain a delicate ecology. Some works in the series were named Transition—here, the quiet surfaces were left undisturbed by stamping or text, echoing a silence that suggested a peace birthed from acceptance. There was a series of jars, the continuation of a fruitful collaboration with Pazhanisamy, fired in the Japanese-style Anagama kiln—their full-bellied forms a perfect canvas for spectacular markings of ash deposits. And the title installation of 71 tea bowls seemed perfectly celebratory! Could it be that Ray Meeker was becoming mellow in his eighth decade?

Concurrent to the 71 Running exhibition ran the Bridges exhibition, at the Stainless Gallery in New Delhi. Featuring the works of over 50 students of the Golden Bridge Pottery, the show highlighted the incredible legacy of the teaching programme at GBP. It was a ringing testament to Ray and Deborah’s immense influence on the field of contemporary ceramics in India. It is notable that their students have not remained working within the GBP aesthetic—many have gone on to forge a distinct voice and vocabulary of their own, and remain at the forefront of contemporary ceramic art practice both in India and abroad.

Some say the world will end in fire

Some say in Ice

Robert Frost, Fire and Ice, 1920

The work in Ray’s show Fire and Ice, 2021 (Centre d’Art des Citadenes, Auroville, and Nature Morte, Delhi), seems to be delicately suspended in a frozen moment of a post-industrial future. In his catalogue essay, Dominique Jacques wrote that “the landscape composed by Ray Meeker is a metropolis crystallized by a cataclysm”; yet, in another essay, Lara Davis writes of this work as “a testament to human resilience”.

Perhaps anger and frustration felt at human inability to synthesize the obviousness of its current path leading to inevitable demise is expressed in clay through the processes of cutting, hammering, pushing, tearing, scraping, and slapping. And yet, even though this tableau of totemic columns is embedded with the bones and fragments of a violent and desolate past, there resides in these works a residual strength, a silent presence, an elemental harmony. Or, as Emily Dickinson wrote, hope is a thing with feathers.

Only through one’s own efforts can the sheer magic of ceramics be thoroughly appreciated; only when one has struggled to give for to raw mud can this prestidigitation be comprehended.

Peter Nagy, Catalogue essay, Subject to Change Without Notice

Ray Meeker is a magician. His supremely sophisticated understanding of material, of form, and of fire is based on a reverence for an uncompromising process, and a deep appreciation of ceramic traditions. The work that he has made is based in equal parts on a heroic fearlessness and the intuitive recognition of an ever-present beauty. Through his seminal work at a scale that challenges the boundaries of this material, what stands out is his embrace of a flirtation with failure, and an ability to assimilate and uncover the teaching contained in any misstep—perhaps a gift of the decade plus spent learning how to build and fire houses in mud. Equally evident, however, is his ability to imbue the smallest work with a potent monumentality, as seen in the 2021 Rough Cut series. Although what dominates the narrative is Ray’s confrontational environmental-themed work, Ray has seamlessly assimilated diverse influences in his work—the raw brutality of Peter Voulkos, the nuanced earthiness of Shoji Hamada, the human relationship with scale in a Richard Serra sculpture, the ‘commitment to truth’ of Golden Bridge Pottery production ware, the spirit and form of Indian temple architecture, the masterful building of the large-scale votive Ayanar horses of South India.

While the subject matter of Ray’s defining work brings attention to the tipping of a precarious balance from creation and evolution towards an inevitable destruction, his work simultaneously embodies a celebration of the art of creating, the decay ultimately subsiding into the regenerative lap of Nature. A transformative fire that is simultaneously an end and a new beginning.

A brief history of Golden Bridge Pottery and the silent ceramic revolution in South India, tracing Deborah and Ray’s journey from California to Pondicherry, the legacy of GBP, its students, fired houses, and its enduring impact, culminating in a poignant reflection following Deborah’s passing in July 2023.

AGNI JATA, the Fired Born documentary: An exclusive film from the ANAB archives (1989), documenting a 1975 experiment in Auroville, South India. From a raw earth house, a terracotta one is magically born.

Vineet Kacker

After graduating as an architect in 1989, Vineet studied ceramics at Andretta Pottery, Himachal and Golden Bridge Pottery, Pondicherry. He attended a post-experience program at UWIC, U.K., and apprenticed with British ceramists Alan Caiger-Smith and Sandy Brown. He is a recipient of the Charles Wallace Fellowship and the Fulbright Grant. Co-founder of the Contemporary Clay Foundation, he has been part of the curatorial team of the Indian Ceramics Triennale, editions 2018 and 2024. He is a current member of the International Academy of Ceramics, Geneva. His work is a part of several collections – notably KNMA, India; Icheon Museum, Korea; the FULE Museum, China; the Mark Rothko Art Center, Latvia. Vineet works from his studio in Gurgaon, India, and in Andretta, Himachal Pradesh