Visit the Wilson Pottery Museum and explore other museums, studios, and ceramic destinations in the US through Ceramic World Destinations (CWD), MoCA/NY’s interactive map featuring over 4,000 ceramic sites worldwide.

I was invited to visit the Bayou Bend Collection and Garden’s Wilson Pottery Collection in Houston, Texas—an unprecedented opportunity. I examine the pots from a potter’s perspective. Cautiously, I walk into the room, the theme song from 2001: A Space Odyssey playing in my mind. The music grows more intense as I approach the table with pottery from all three Wilson sites.

They sit there as if expecting me, and at that moment, I wish they could share their journey with me. They are all Wilsons; some are tall, short, thin, and wide; others have meticulously crafted attached handles with lustrous glazed surfaces, as if they have just emerged from the kiln. Some are broken, others are weathered with sections of glaze missing. I look for blemishes and tell-tale marks that identify one potter’s style from another. I note the compression points on the interior floors of the pots and the spacing of the interior throwing rings, hoping to see variations that indicate hand size or the steadiness of the potter’s effort in pulling the clay from bottom to rim. I also check for signature styles on the rims.

The interior floor (bottom) of pots attributed to the Wilson Potters. All examined pottery was thrown on the potter’s wheel, which creates distinct markings in the clay during the initial throwing process. Compression marks on the floor of pots are unique to each potter. Most of the pots I examined were similar to Figures 1 and 2. Although Figure 4 was classified as a Wilson pot, I did not find any others in the grouping with a similar pattern

Jug handles indicate specific information about the potter’s origin. Scholars believe that handles attached shoulder-to-shoulder are characteristic of the Edgefield (southern) region, while those attached rim-to-shoulder are associated with Ohio or other northern states. Most of the jugs with rim-to-shoulder handles from Durham-Chandler-Wilson Pottery have been attributed to Isaac Suttles of Ohio.

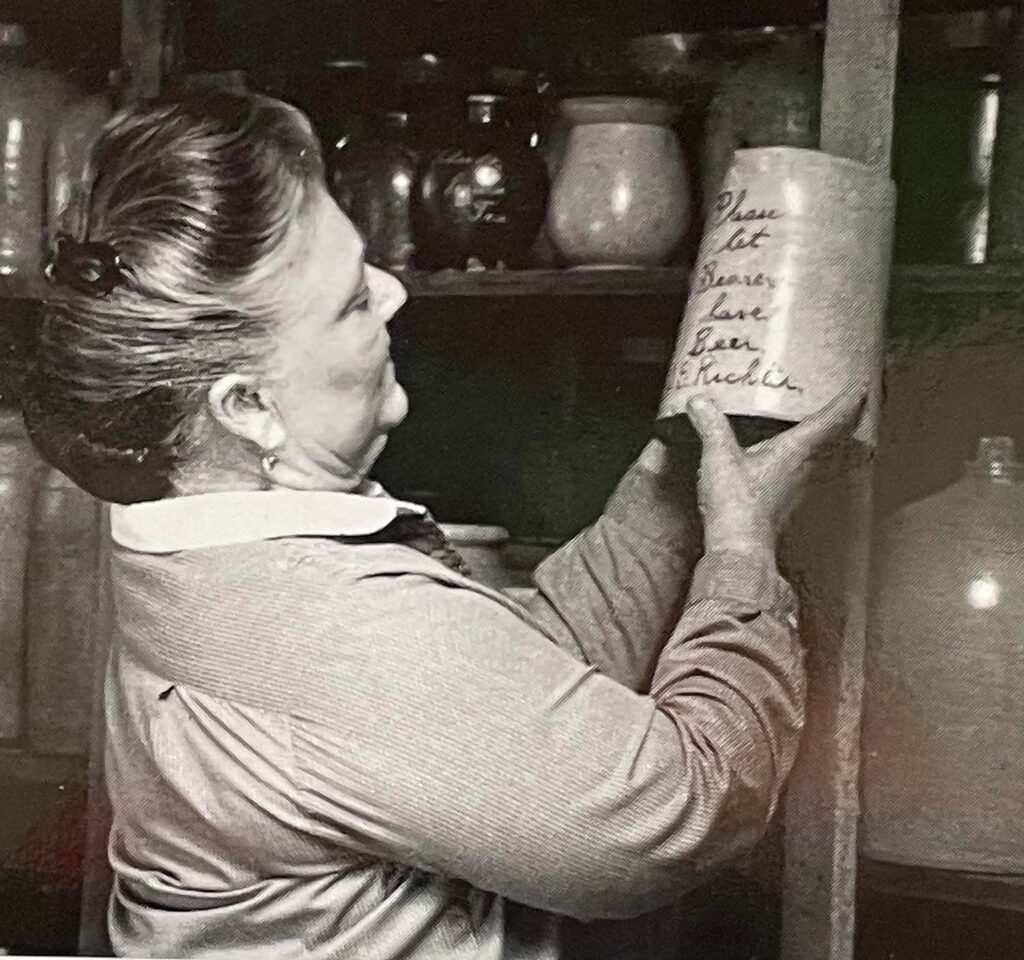

As I study the Wilson pots firsthand, I begin to think about how their history came back into view—and the scholars and potters who ensured these stories were not lost. Dr. Georgeanna Greer, a prominent Texas pottery scholar and pediatrician, played a crucial role in rediscovering the Wilson Potteries after the sites had been dormant for more than fifty years. I discovered the extent of her research when I visited historical societies in East Texas. I was both overwhelmed and excited to discover letters she had written to local archivists. In 1981, she published the Art and Craft of Utilitarian Potters. Other documents and audio recordings from James Wilson, Jr. and Sarah Duncan’s descendants shared oral histories of the Wilsons’ journey from slavery to entrepreneurship. Harding Black, a Texas potter and Dr. Greer’s mentor, assisted her on visits across Texas searching for abandoned pottery sites.

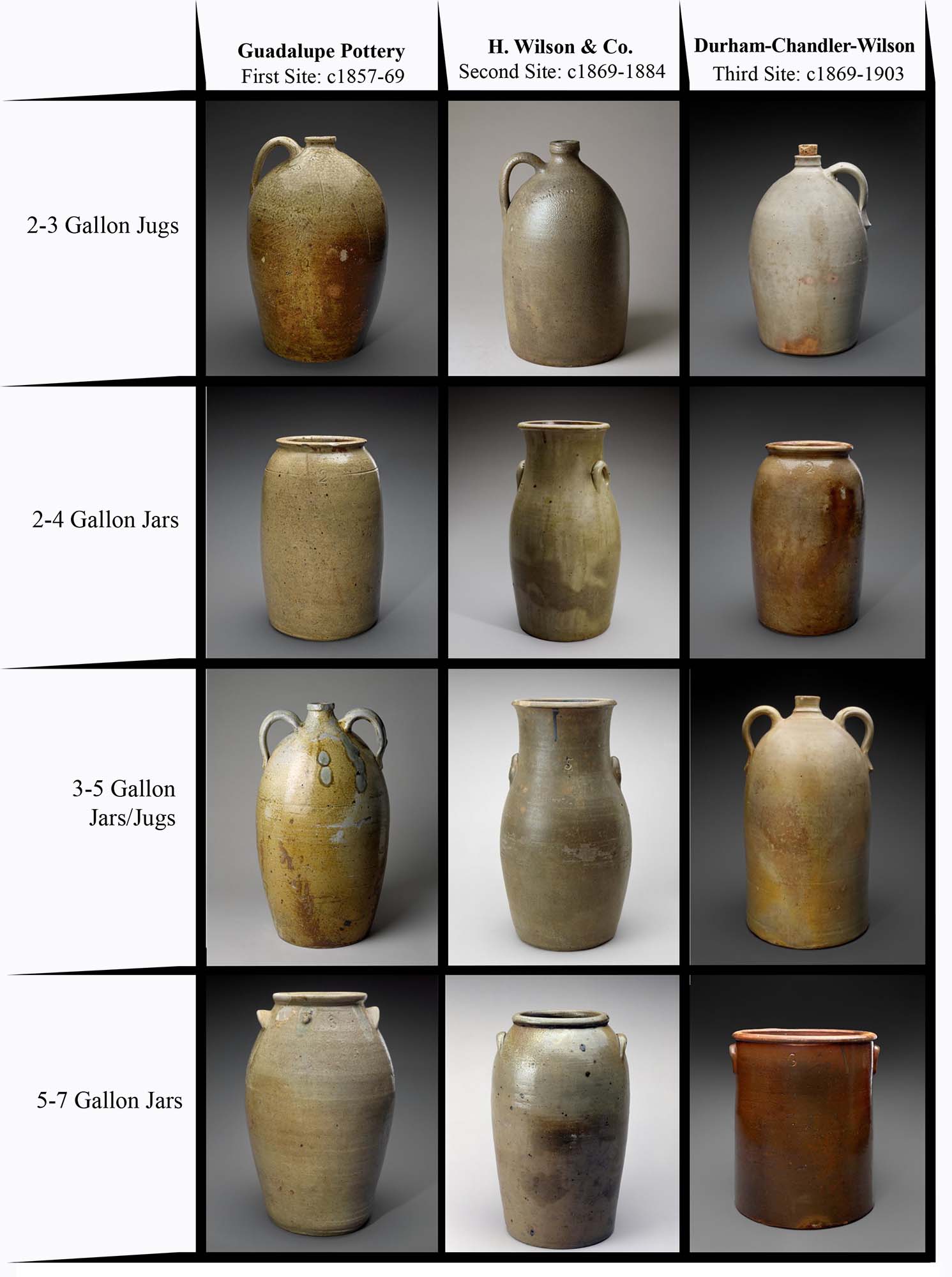

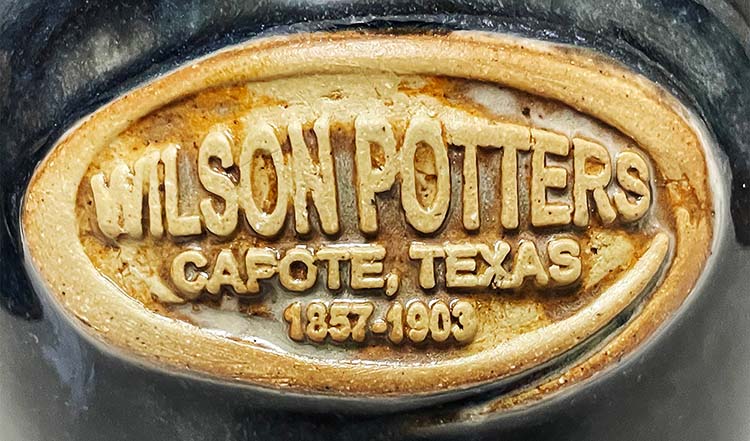

The three Wilson Pottery sites in Capote, Texas operated collectively from 1857 to 1903, spanning nearly 50 years. Capote is located approximately 48 miles east of San Antonio and 12 miles east of Seguin, Texas. These sites have been identified and documented by local scholars and the Texas Historical Commission.

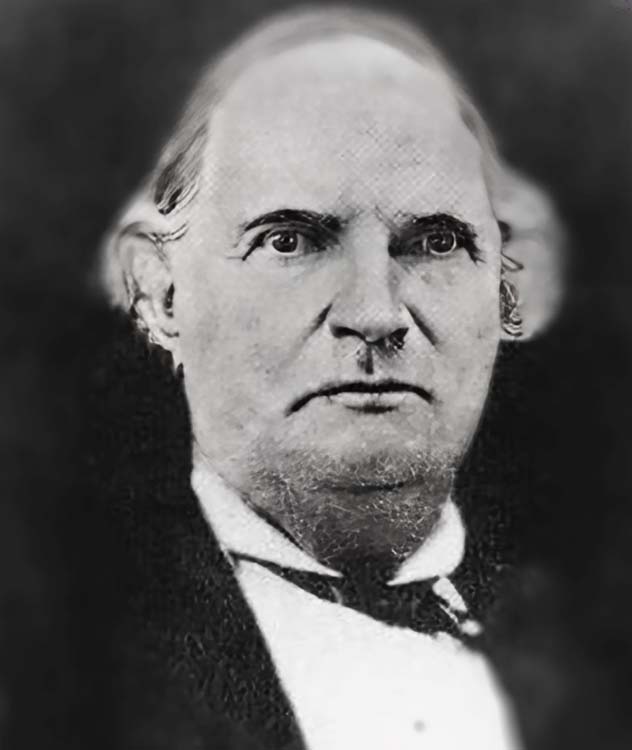

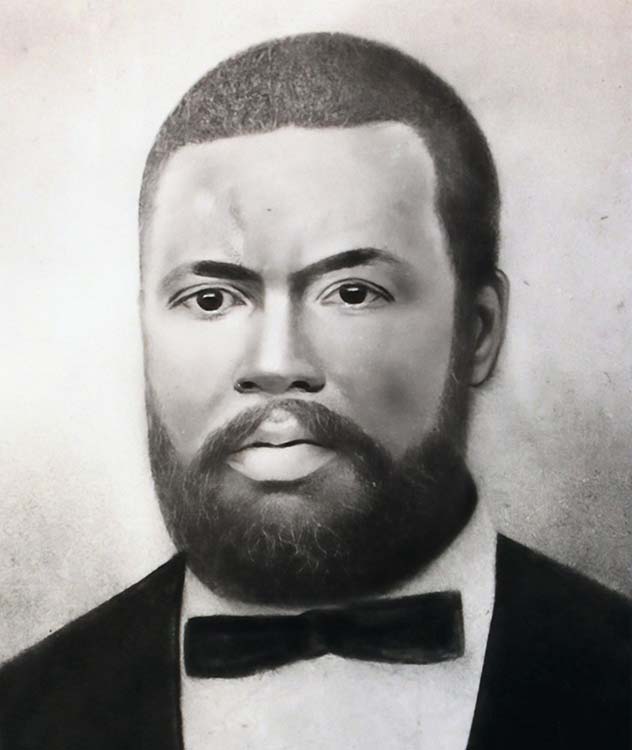

Guadalupe Pottery (41GU6)* was the first Wilson pottery site, established by John McKamie Wilson (Figure 17), a Presbyterian minister, along with his enslaved and itinerant potters. He is believed to have founded the first stoneware company in South Central Texas. H. Wilson & Co. Pottery (41GU5)* was the second site, owned by Hiram Wilson (Figure 18) and other formerly enslaved potters from the Guadalupe site.

The third Wilson Pottery (41GU4)* was the Durham-Chandler Pottery, operated by Marion "MJ" Durham and John Chandler, a formerly enslaved potter from the Edgefield District of South Carolina. Marion “MJ” Durham was himself of the renowned Durham Pottery Dynasty of that same district. After Hiram’s death in 1884, H. Wilson & Co. was believed to have merged with Durham-Chandler, forming Durham-Chandler-Wilson. In 2018, Tarrant County College District awarded me a faculty leave to study H. Wilson & Co. pottery in Capote, Texas, where I discovered it had been a sister company to Durham-Chandler and a descendant of Guadalupe Pottery.

*41GU6, 41GU5, 41GU4 refer to the official state and archaeological site designation for each site

The potteries in Edgefield, South Carolina, were the first stoneware factories in the southern United States. Abner Landrum established the first stoneware factory around 1815, and by the 1850s, it had developed into an industrial empire, with enslaved people working at every level of the production process.

Sources indicate a connection between Guadalupe Pottery and the Old Edgefield District, South Carolina, through Marion “MJ” Durham and John Chandler. Durham and Chandler arrived in Texas around the same time the Guadalupe Pottery opened in Capote, Texas. Since John McKamie Wilson’s family was from Mecklenburg, North Carolina, he was likely aware of the industrial pottery system in Edgefield. He may have been acquainted with the Durhams, who also had ties to Mecklenburg. Wilson moved from Mecklenburg to Missouri before relocating his family and slaves to Texas around 1857

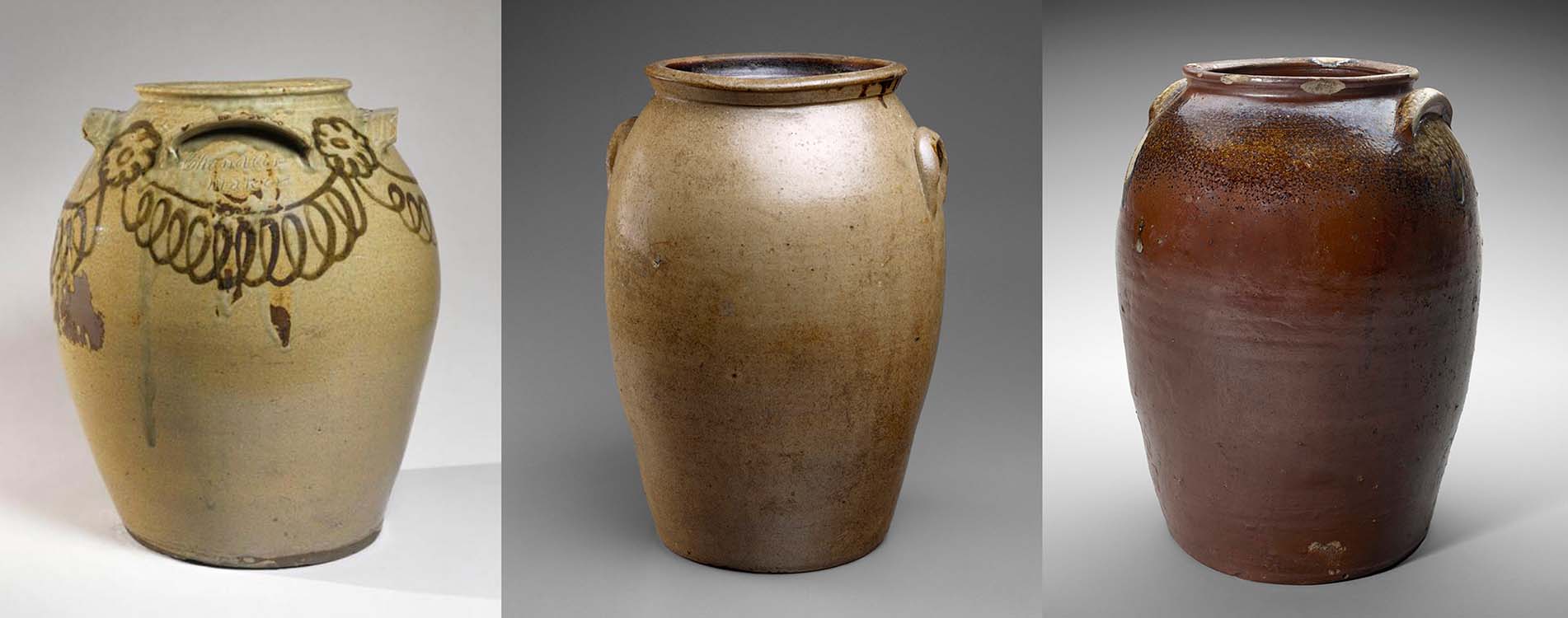

Figures 13–15. Side-by-side comparisons of Thomas Chandler Pottery of Edgefield with the Guadalupe Pottery and H. Wilson & Co. Pottery.

John Chandler of Durham-Chandler Pottery is believed to have been the formerly enslaved apprentice of the renowned Edgefield potter, Thomas Chandler. Thomas Chandler, an outsider from Virginia by way of Baltimore, Maryland, married Margaret, the sister of Marion “MJ” Durham, which awarded him privileges in the close-knit pottery community in Edgefield. Durham assisted with settling Thomas Chandler's estate, which may have freed John upon Chandler’s death. Since Durham and Chandler moved to Texas before 1861, Durham may have been an initial investor in John McKamie Wilson’s Guadalupe Pottery. If accurate, Durham and Chandler may have trained Wilson’s enslaved potters, Hiram, James, Wallace, and others. If my theory is accurate, the legacy of renowned Edgefield potter Thomas Chandler took root and flourished in Texas.

The wheel-thrown pots attributed to the Guadalupe Pottery appear to be heavily influenced by the Edgefield, South Carolina style, particularly the ovoid body and shoulder-to-shoulder handles on the jugs. The waster pile at the old Guadalupe site yielded examples of both alkaline and salt glazing techniques, which appeared to have been fired in the same kiln. Figure 22, for instance, appears to show a salt-glazed surface, though the drips resemble the gloss and color of an alkaline glaze.

H. Wilson & Co.'s body style is similar to Guadalupe Pottery, except for its horseshoe handles, which sit closer to the surface of the pot, and its signature stamp on the pottery. A close examination of pot and “waster pile” sherds indicates that the salt process was the only surface treatment they used. As noted earlier, the heat and pots in the kiln can yield variations, producing different-looking pots even when fired together. Insufficient heat often produces a rough, dull surface, a quality I observed at Bayou Bend.

Durham Chandler Wilson (41GU4) shows the most extensive range of individualism among the three companies, especially in the treatment of jug handles. Scholars attribute the shoulder-to-shoulder handle connections to Edgefield influences, while the rim-to-shoulder style is associated with the northern states, such as Ohio. Many containers with the rim-to-shoulder style are attributed to Isaac Suttles, the Ohio potter believed to have introduced salt glazing techniques to the Guadalupe Pottery. Many of the pot surfaces do not clearly appear to be alkaline or salt, suggesting that heat work in the kiln was a significant factor in the maturation of the glaze. Under-firing resulted in a rough, dull surface.

Figures 8–11. Figure 8 illustrates the fluidity of an alkaline glaze; Figures 9 and 10 show the softness of salt glazing; Figure 11, though listed as salt, may have been fired in a different kiln atmosphere.

The story of the Wilson Potteries extends beyond the pots themselves, shaping the cultural memory of the region and prompting efforts to preserve their history. The City of Seguin, Texas, embraces the legacy of the Wilson Potteries. In 1985, the Texas Historical Commission erected a Historical Marker outside the Capote Baptist Church. From 2007 to 2009, the Texas State University Center for Archaeological Studies conducted research at the Durham-Chandler-Wilson 41GU4 site. Afterwards, the site was backfilled to protect the artifacts.

Descendants of Hiram and James Wilson celebrate their triennial Family Reunion in Seguin. The Wilson Pottery Foundation sponsors two annual events: a gala each spring and the Wilson Pottery Show during the Annual Pecan Festival in the Fall. I found articles in the Seguin Gazette Newspaper dating from 1960 to 2025 documenting the legacy of the Wilson potters.

The Sebastopol House in Seguin, Texas, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was built of limecrete in 1854. In 2013, it became the home of the Wilson Pottery Museum, established by the Wilson Pottery Foundation. Over the past decade, the museum has grown into a haven for preserving and interpreting Wilson pottery. At its 10th anniversary celebration in 2023, the Foundation was presented with a six-gallon First Site Pot by the friends of John and Edie Hundley. The event brought together descendants of Hiram and James Wilson alongside descendants of their enslavers, underscoring the shared history and enduring legacy of the Wilson Potteries.

In 2013, the Wilson Pottery Foundation opened the Wilson Pottery Museum at the historic Sebastopol House in Seguin, Texas. During the celebration of the tenth anniversary, the Friends of John Hundley presented the museum with a pot attributed to the Guadalupe Pottery, 41GU6 site.

The annual Wilson Pottery Show began in 2002 under the supervision of Richard Kinz and John Gesick. Antique pottery collectors from across Texas gather to showcase and trade their wares, offering guidance to visitors seeking information on their family's heirlooms, such as grandpa’s jugs. I offer “Throwing on the Wheel” Photo opportunities for visitors, and the pots they make are fired and auctioned off the following year.

Building on this legacy, my faculty development leave resulted in an exhibition that both honored the Wilson potters and reintroduced their story to contemporary audiences. The highlights of the exhibition were presented in posters identifying the potters who worked at either one or all three pottery sites. The exhibition also featured 20 commemorative pots embossed with "H. Wilson Legacy Revisited," a label that has since been retired. The new title, “The Wilson Potters of Capote, Texas, 1857-1903,” celebrates all the potters who may have worked at the Wilson potteries.

As Professor Emeritus at Tarrant County College District, Fort Worth, Texas, I focus on creating commemorative jugs honoring the Wilson's legacy and continuing to search for unknown and under-acknowledged African American potters of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In our ultra-glossy, refined ceramic culture, most viewers would not give 19th-century stoneware a side-eyed glance, but its legacy, built on the backs of enslaved, free, and itinerant potters, shall endure.

The research continues at Bayou Bend as identifiable data from the interior of pots have broadened the spectrum for scholars to date pieces and eventually assign potters to a specific group of pots. I am honored and grateful to the staff at Bayou Bend for providing this unforgettable experience.

Earline M. Green is a career educator and renowned ceramic artist with artwork in public and private collections. She is recognized internationally through advertisements for Paragon Kilns, highlighting her Legacy Ceramic Tile Murals. She has artwork published in Contemporary Black American Artists, 500 Prints in Clay, 500 Tiles, and Image Transfer on Clay books. Visit her website