Ceramic Supply

Pittsburgh

One Walnut Street

Carnegie, PA.

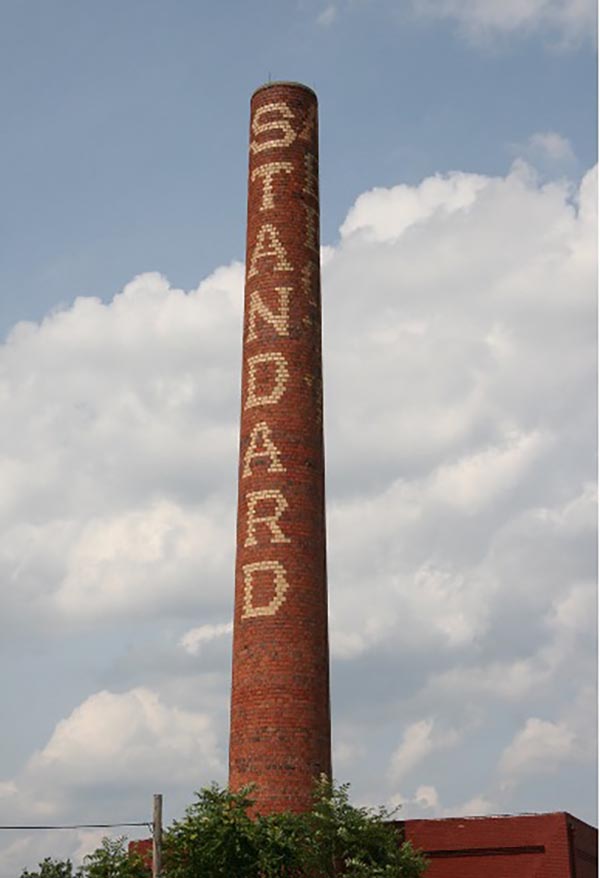

Standard Clay Company, based in Pittsburgh, is a fourth-generation manufacturer of wet clay bodies, slips, and glazes. Its products are distributed through a network of over 50 partners across the eastern United States, with an expanding presence internationally. The company's gallery, ClayPlace@Standard, hosts multiple exhibitions annually and served as a showcase venue for the 2017 NCECA conference.

Part of what makes Standard Clay such a compelling company is the way it mirrors the art world’s ethos of family and community. Ceramic Supply Chicago and Ceramic Supply Inc., both subsidiaries of Standard Clay and based in the New York area, share this spirit, with staff fostering genuine relationships with artists—not just as customers but as fellow participants in a larger creative enterprise. The heart of this communal pulse, however, lies in Pittsburgh, where Standard Clay’s headquarters has, for generations, remained firmly rooted in the Turnbull family.

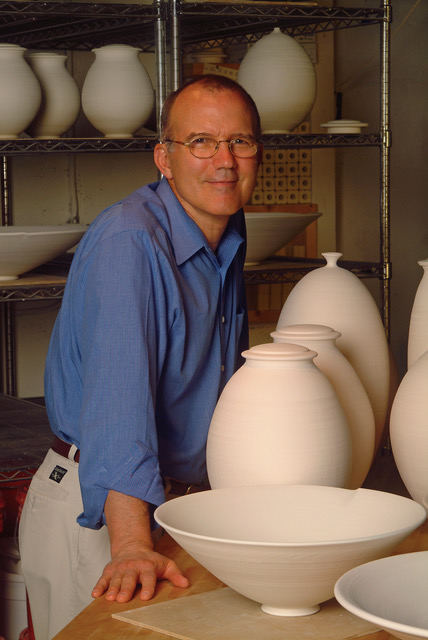

Headed by Jim Turnbull, who succeeded his father James, Sr., and now works alongside his son, Graham, Standard is synonymous with the Turnbull name. Jim, with his vibrant charm and irrepressible curiosity, forges connections with artists across continents. Graham, meanwhile, steadily mans the helm. Yet the Turnbull narrative isn’t simply one of linear succession.

There is a third figure, a prodigal presence of sorts, who completes the family triangle: Tom, the other son of James, Sr., who once ventured away to carve out a path of his own. His life, however, has always circled back to clay. As he embarks on a retrospective of his life’s work, he finds himself on a reflective expedition, one that resonates with anyone who has ever pondered the enigmatic question of what it means to dedicate a life to art.

“I was in ceramics before I was born,” Tom says. “My father came home from a stint in the Merchant Marines in 1947 and got a job as a salesman for O. Hommel Company, a manufacturer of porcelain enamels. I was born in 1951.”

Tom’s earliest relationship with clay was not one of artistic fascination but of labor. His father, James, Sr., stumbled upon the ceramic world through the pragmatics of industry: his work brought him into contact with pottery companies that needed clay in large, utilitarian quantities.

It was during a conversation with art teachers in Pittsburgh’s public schools—educators in need of a reliable clay supplier—that James, Sr. first glimpsed the potential. He procured industrial clay, repackaged it into smaller amounts, and soon began experimenting with his own formulations. From these humble, almost incidental origins, Standard Ceramic Supply Company was born.

Like many children in family enterprises, Tom was swiftly conscripted into service. “I spent all of high school stacking boxes of clay.” By graduation, he was drained. “I had an uncle who retired about that time who had never nurtured any interests outside of work. He sat down at the kitchen table and never got up. I didn’t want to be him. I wanted a reason to get up in the morning.”

Turning away from the business side of clay, Tom Turnbull turned to his father for guidance of a different kind. “I wanted to learn,” he says, “and I couldn’t wait to get out.” James, Sr., ever resourceful, connected Tom with an old friend: Charles Counts, the author of Common Clay, who had recently returned to Lookout Mountain, Georgia. There, Tom enrolled in an eight-week course that would alter his trajectory. “It was sensational,” he recalls. “I became a potter.” Apprenticing under Counts and folk-art potter Legatha Walston, he honed his craft but soon grew bored. A nearby horse farm captured his attention, and before long, he was spending more time at the stables than at the wheel.

Tom worked on the farm, eventually driving horses to racetracks across Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Illinois. Enthralled by the world of racing, he convinced his father and brother, Jim, to invest in a racehorse. But when the horses moved north, Tom stayed south, making Fort Lauderdale his refuge—spending time by the beach and practicing pottery in a storage garage.

At twenty-seven, Tom experienced what he calls an unexplainable epiphany. 'I woke up one morning and said, ‘This is nuts! I need an education.’' Feeling behind his peers who had built careers and families, he was determined to catch up and enrolled in a local community college while juggling construction jobs. A year later, he earned a full scholarship to New York University’s Industrial Arts program. After his studies, he briefly worked in sales at Standard before a stint in music promotion in Nashville.

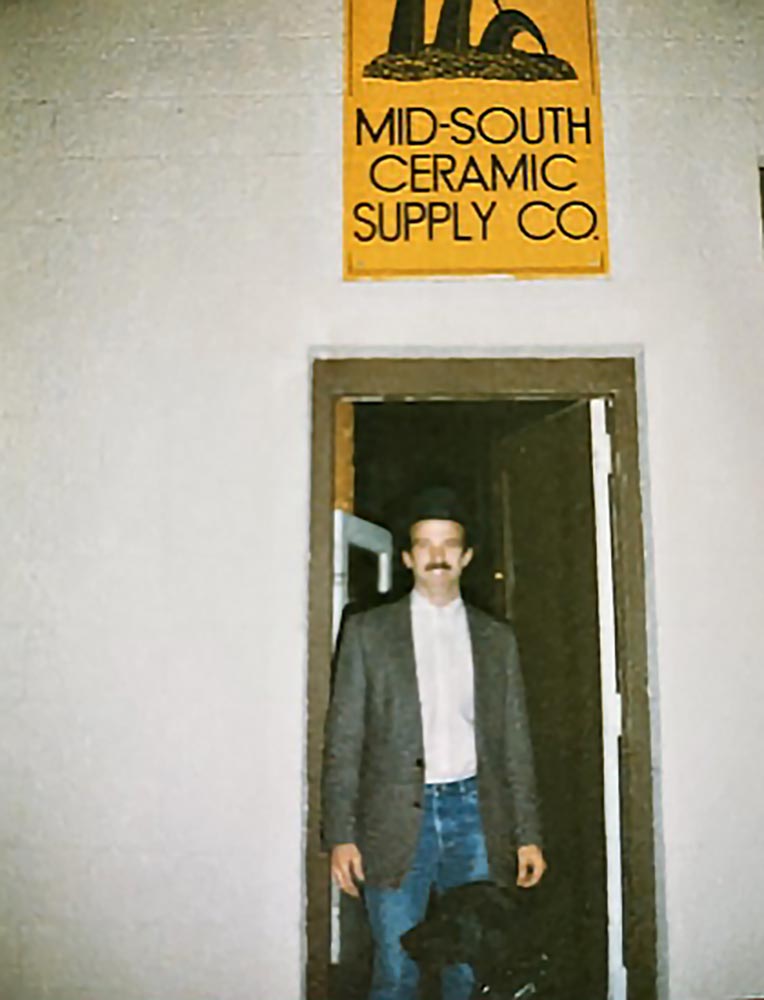

But there, he saw an opportunity: “I looked around Nashville,” Tom recalls, “and saw that there wasn’t any ceramics presence there.”

Seeing a gap in the market, he founded Mid-South Ceramics, serving as a distributor for Standard’s clays and glazes. The business brought him back.

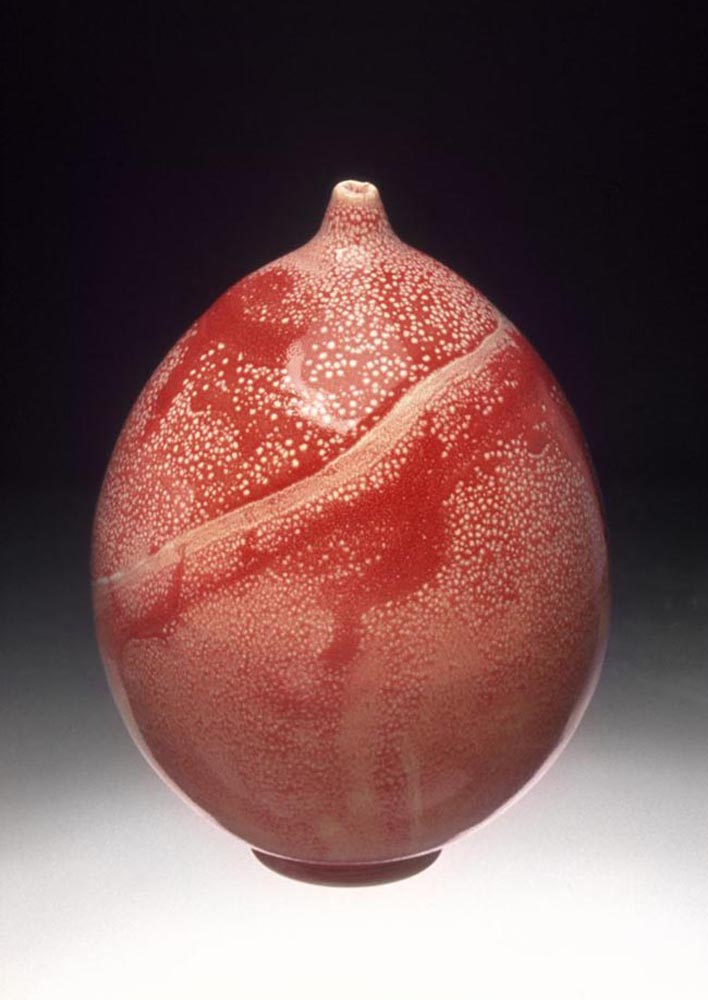

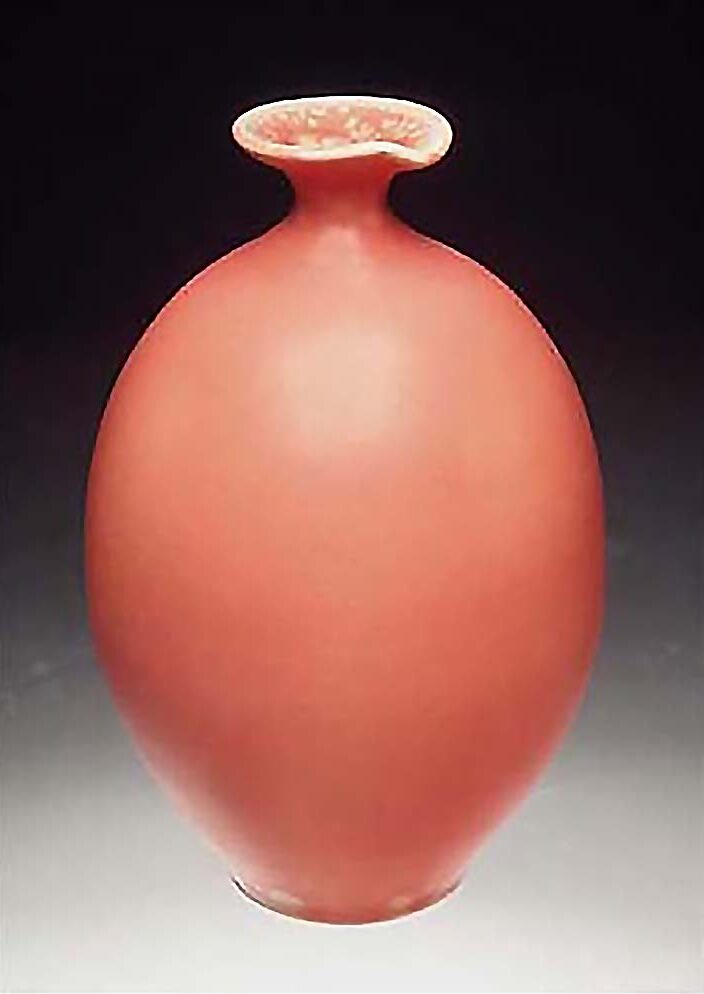

Tom noticed his customers struggling with inconsistent glaze results and saw a need for a reliable product. Teaming up with industrial coatings expert Dr. Richard Eppler, he developed and patented the Opulence Glazes line—an innovation that simplified the glazing process. “All you have to do is add water, and you have a state-of-the-art glaze.” His growing expertise in glazes eventually led him to become the U.S. agent for the Australian minerals company RZM Zircon.

Mid-South Ceramics flourished, but after thirteen years, Tom was ready for another change. In 1999, he sold the business to Esmalglas, a Spanish ceramic materials company, and at forty-eight, he retired to focus on his pottery full-time. “I finally had a reason to get up in the morning,” he says. “To go look in the kiln.”

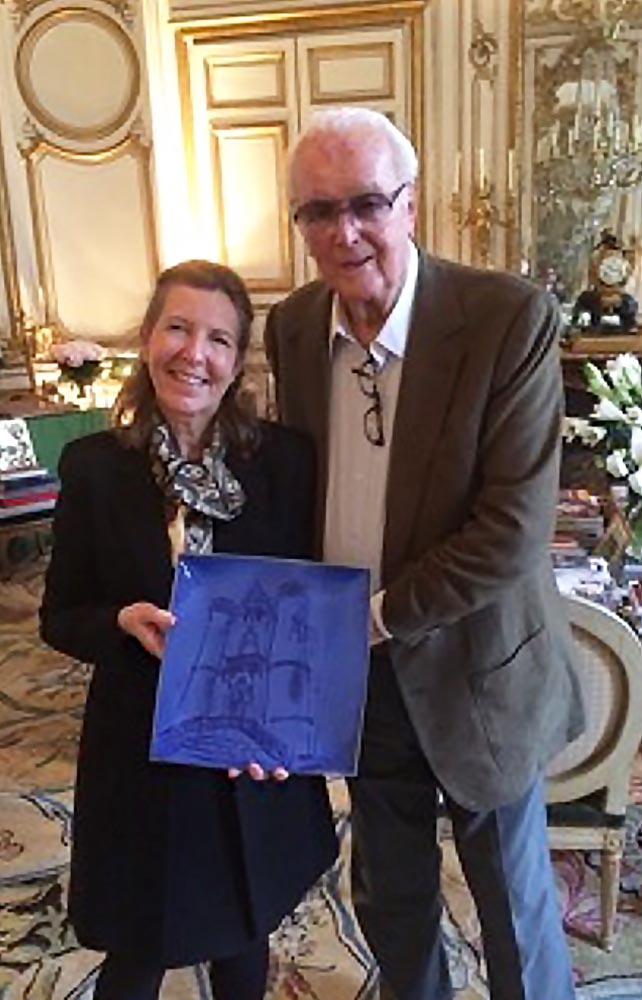

His first outdoor show ended with a surprise: he was awarded Second Best. Subsequently, the judge, the Art Director of the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, invited him to display more than thirty pieces in the CDC’s Global Communication Center. Collectors took notice, including Friends of Chantilly, a nonprofit organization that preserves art at the Château de Chantilly in France. The organization, backed by the late fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy, selected one of Tom’s pieces for Givenchy’s permanent collection.

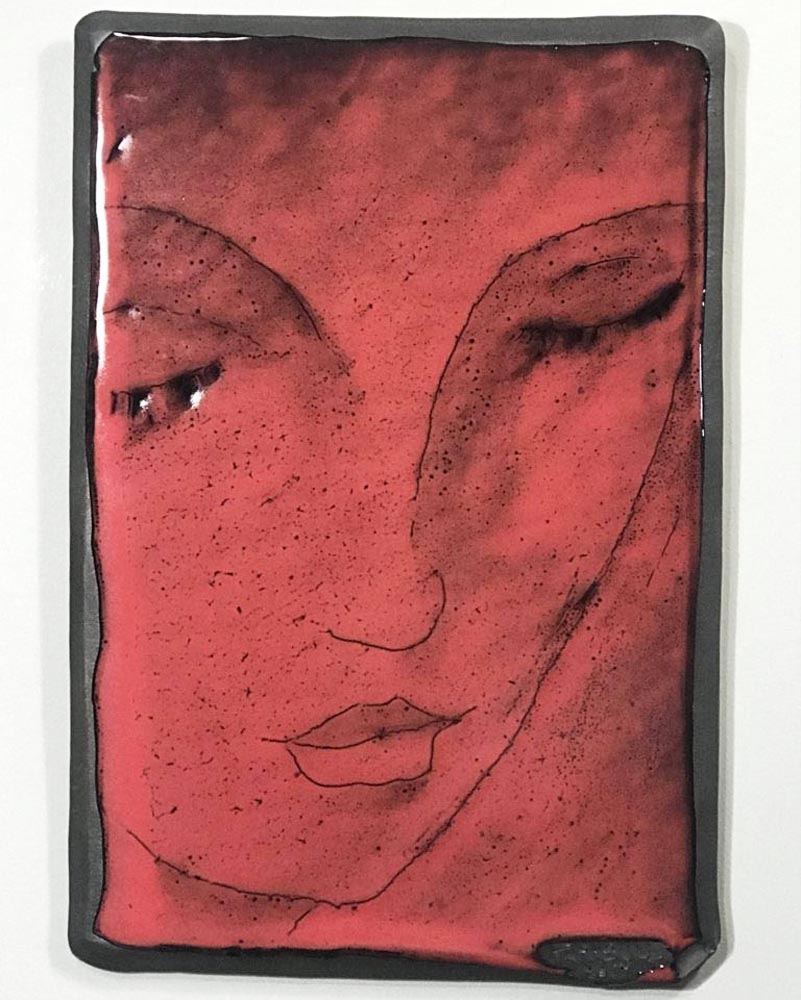

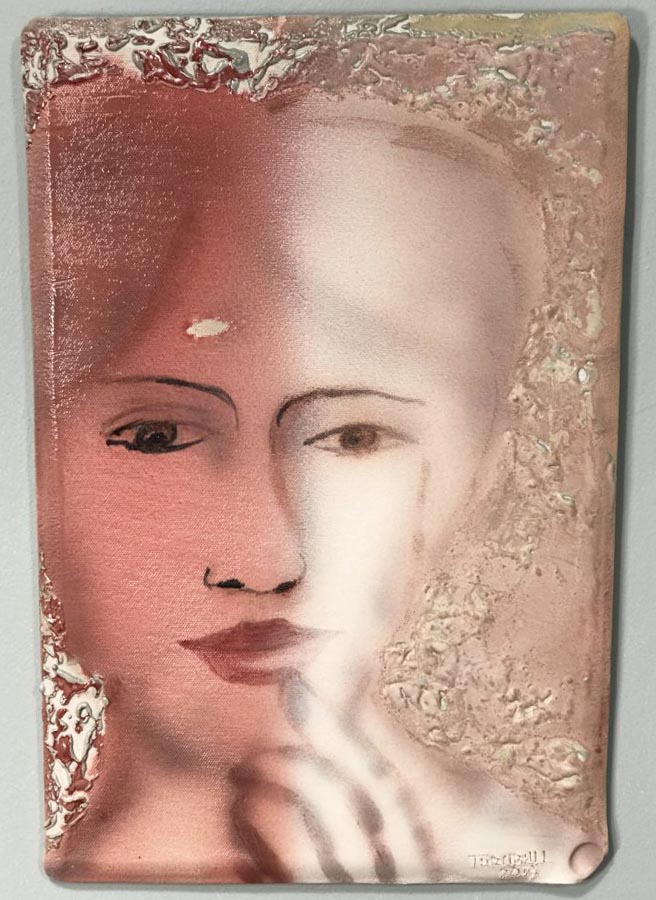

“I am a craftsman,” Tom says. “It is deeply in my DNA.” His work spans wheel throwing, slab building, and occasional extrusion, though he makes one distinction: “I’m not a sculptor.” Lately, he has turned to painting glazes on 12-by-18-inch tiles, exploring new possibilities. Currently, he’s working on a tile installation of The Last Supper for West End Methodist Church in Nashville, featuring women at the table—an intentional reimagining of tradition.

Tom’s journey—from leaving the family business to apprenticing under master potters to detours in horseracing, education, and music promotion, then running his own company and developing a proprietary glaze—has been marked by unexpected turns. But this past year brought a turn he never anticipated.

Last October, he joined his brother Jim and sister Joanne for a long-overdue sibling reunion in New Mexico. The occasion was weighted with difficult news: he has Stage 4 pancreatic cancer and is now facing his imminent death. “The most powerful piece of information you can be given,” Tom says, “is to know when you are going to die.” On a practical level, it allows you to get your affairs in order. But on another, it stirs questions—about the body, the mind, and what lasts. “I don’t have much use for this body anymore,” he says.

What he does find purpose in, even now, is his family—especially his six grandchildren. “I was born to be a grandfather,” he muses. “When Eliot, the eldest, was born, I had the opportunity of a lifetime to be a part-time, regular caregiver for him.” Three of his grandchildren live nearby in Nashville; the others are in Charleston, South Carolina.

In pondering what comes after death, he often returns to the permanence of his work. “Pottery lasts,” he says. “It’s common to find pottery shards that are 10,000 years old. It’s what the archaeologists are looking for!”

Teaching, too, offers consolation. “I teach the passion and the aesthetic of clay,” he says. Passing on his knowledge feels like planting seeds, each student carrying a spark of his craft into the future. This sense of lifelong learning resonates deeply with him, much like Michelangelo’s late reflection: “I regret that I have done so little for my eternal soul and that I am just beginning to learn the alphabet of my craft.” Tom echoes the sentiment, saying, “God, I’d like to have another lifetime. I’m just beginning to figure things out.”

Yet, in these past months, he has found clarity. “I don’t need a tombstone,” he says. “My tombstone will be my work.” His legacy lives on—preserved in collections, held in the hands of students and family, and rooted in the lasting imprint he has left on his community.

Visit Ceramic Supply - Pittsburgh at One Walnut Street, Carnegie, PA, and learn more about Standard Clay on their website.